The dojo after dark: Aikido's complicated relationship with alcohol

Why the post-training drinks tradition reveals deeper questions about community, performance, and what we're really practicing for

TL;DR: The debate over alcohol in aikido reveals tensions between tradition and optimization, community bonding and individual performance, cultural authenticity and personal choice.

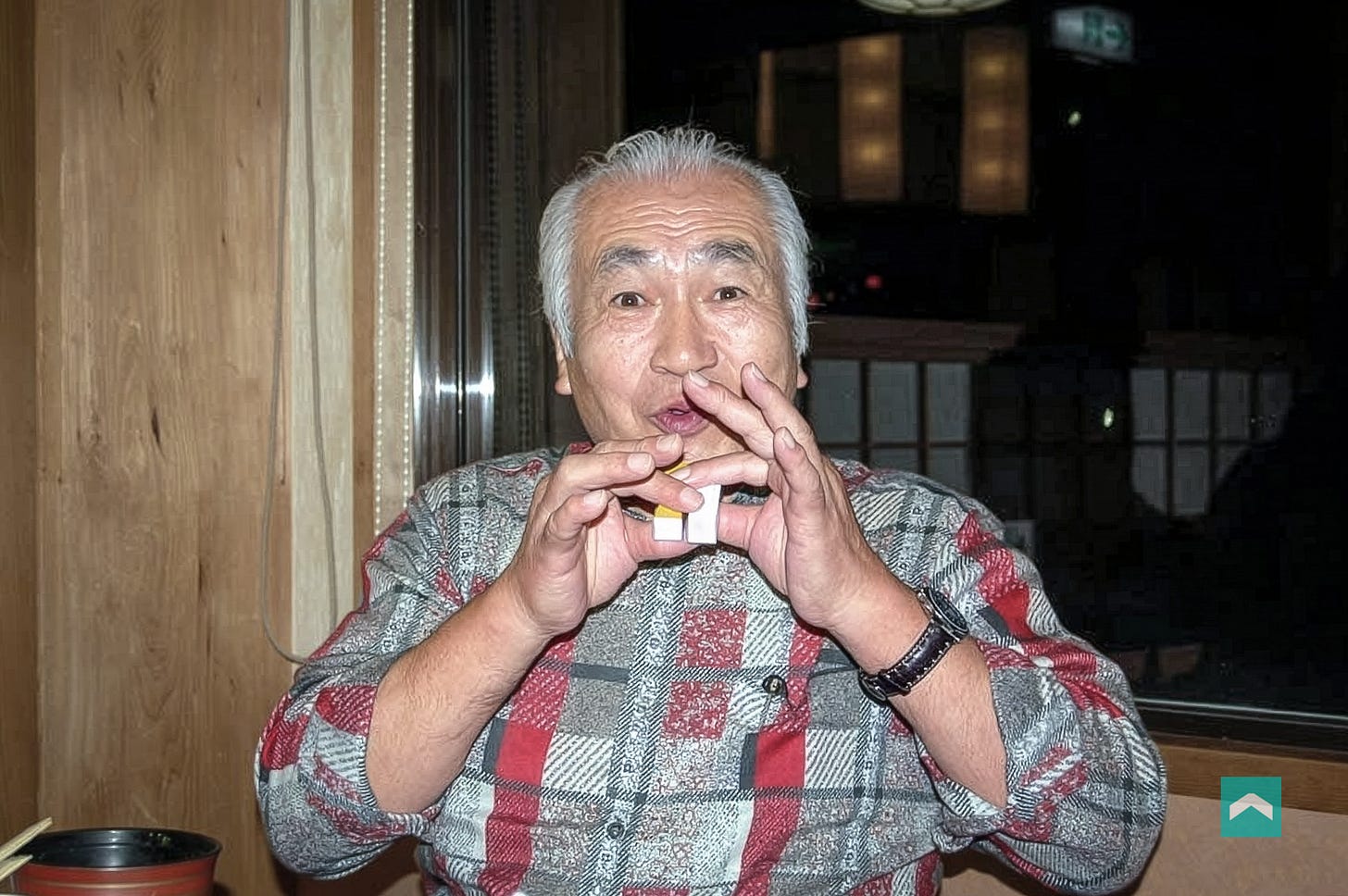

The bottle of țuică appeared in the Romanian dojo changing room within minutes of training ending. By the time we had showered and changed, the potent plum brandy had already disappeared among the aikidoka.

This moment perfectly captured aikido's unspoken relationship with alcohol - instant camaraderie mixed with cultural tradition, while raising uncomfortable questions about what we're really doing when we train.

This experience led me to dive deep into a fascinating Reddit discussion that reveals the intersection of tradition, spirituality, performance, and human nature in modern martial arts practice.

The founder's complicated legacy

The alcohol debate often centers on O-Sensei, with practitioners citing his supposed teachings about having "no desire but to practice aikido." Many interpret this as calling for monastic dedication that would naturally exclude drinking.

The reality is more human than the mythology suggests.

As one longtime practitioner and researcher pointed out in the discussion:

"Morihei Ueshiba never, ever, condemned drinking. He did drink less as he got older, as many people do, but some of that was related to his liver problems. He never stopped drinking."

His designated successor died in a drunken brawl. His official 10th Dan injured his back falling down stairs while intoxicated. Even his son Kisshomaru struggled with alcohol dependency.”

These aren't moral failings - they're reminders that aikido founders were human beings navigating the same tensions we face today.

The performance question

The practical tension every serious practitioner faces comes down to optimization:

"I'm not paying money for a seminar to feel like shit on the mat because I drank some beer the night before."

It’s ultimately about investment and return. If you're spending time, money, and physical effort improving your skills, why voluntarily impair your ability to learn and perform?

Modern research confirms what most athletes know intuitively - alcohol significantly disrupts the body's ability to adapt to training, essentially switching off the biological triggers that lead to improvement.

Yet the counterargument carries weight too. Some of the most profound aikido conversations happen not on the mat, but around the table afterward, when formal hierarchies soften and genuine connection occurs.

Some argue that aikido should be proof against any condition, that a few drinks or a restless night shouldn’t matter if the principles are truly embodied. A friend who trained as uchi-deshi under Isoyama Sensei told me about being ordered to drink a bottle of sake before practice. The lesson, supposedly, was that a samurai must be ready to perform in any condition.

The cultural divide

In Japan, where aikido originated, drinking after training isn't just accepted - it's woven into the social fabric. As one practitioner noted:

"Most seminars in Japan include a heavy amount of drinking - it's one of the few safety valves in Japanese society."

This creates tension for Western practitioners caught between authentic cultural practice and personal optimization. Are you honoring the art's roots, or importing cultural baggage that doesn't serve your goals?

The question becomes more complex when you consider that many aspects of traditional Japanese training culture - the emphasis on endurance over technique refinement, the rigid hierarchy, the resistance to questioning methods - don't necessarily translate well to contemporary learning environments.

The Sobriety Spectrum

Perhaps the most powerful voices in the discussion come from those who've made the decision to abstain entirely. Their stories reveal both the social pressure that exists and the clarity that comes from stepping away:

"I lost two teachers to alcohol — one died, the other became impossible to train with. So for me, it's serious."

"Aikido makes me want to be deeply connected to reality, so blunting my senses is less desirable."

These aren't judgmental pronouncements but personal testimonies that highlight an uncomfortable truth: for some practitioners, the social drinking culture of aikido becomes genuinely problematic.

The individual choice

For some practitioners, a drink after training feels harmless, even natural. For others, it directly undermines their purpose on the mat. The line is deeply personal. What refreshes one person can dull another’s clarity. The key isn’t to follow a fixed rule but to recognize that each choice shapes our practice. Respect for the art includes respect for how we care for our own body and mind.

Listen to yourself and do what serves you. But also recognize: alcohol is a dangerous and cunning beast. For anyone wrestling with dependency, it clouds judgment, twists self-perception, and makes sincerity nearly impossible. Ignoring that reality risks turning practice into pretense.

Finding your way

Beyond culture and preference lies the sharper question: what are we really training for? If aikido is meant to cultivate presence and honesty, then anything that clouds those qualities is not neutral. Community bonding can be valuable, but not if it pulls us away from clarity.

A balanced approach is to treat alcohol as we treat any principle in practice: stay centered, remain aware of your situation, and respond according to genuine needs rather than external pressure. For some, that may include sharing a drink. For others, it means clear boundaries to protect training and well‑being.

If drinking is a regular pattern, ask a close friend you trust to tell you honestly whether they see it as a problem. If their answer unsettles you, it may be time to seek help.

The question isn't whether drinking after training is right or wrong. It's whether your choice serves the person you're trying to become through your practice.