The children's games that became survival skills. Part 2.

How war taught a Ukrainian instructor what aikido exercises actually prepare you for

This story emerges from conversations between Ukrainian aikido instructor Oksana Kozakevych and Saša Dokiai from Aikicraft. Rather than extracting her experience, we've collaborated as equal partners—she leads the narrative, I provide writing support and platform. What follows is her insight into what war taught about aikido that peaceful practice never could.

If you haven't read Part 1, start here for the full story.

TL;DR: During tactical military training, Oksana discovered that the "childish" exercises she'd been teaching for years weren't preparation for martial arts—they were survival skills disguised as games. Her revelation transforms how we understand aikido's true purpose and practical value.

The moment everything clicked

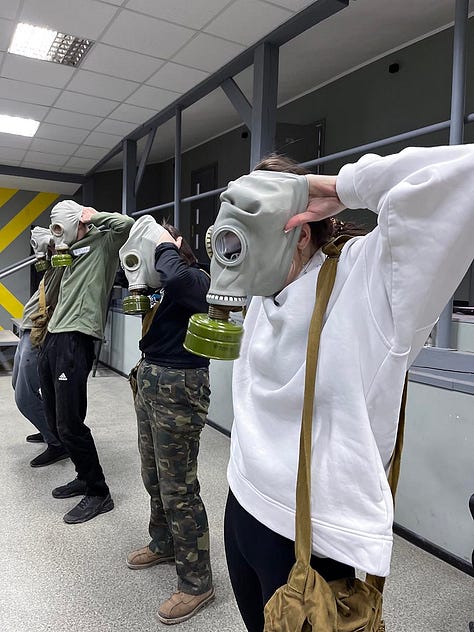

I was lying on the ground during a tactical training exercise, having just practiced dropping to avoid incoming fire, when the instructor said something that stopped me cold:

"These movements you're learning—falling, crawling, moving low—if you've done any martial arts training, especially the kind with ground work, you'll find this comes naturally."

That's when it hit me. The "children's games" we'd been practicing for years—crawling under partners, rolling in every direction, learning to fall without fear—these weren't just exercises for physical conditioning. They weren't preparation for more advanced aikido techniques.

They were the techniques.

Every time we'd had students crawl under imaginary bridges, we were teaching them how to move undetected under fire. Every forward roll we practiced was training the body to hit the ground safely when explosions knocked you down. Every exercise where children jumped over their crouched training partners was developing the spatial awareness needed to navigate obstacles in crisis.

During my second tactical medicine course—the serious one with veterans—I realized I wasn't struggling like other participants. When they told us to drop and crawl, my body knew how to do it efficiently. When we practiced rapid position changes, the movements felt familiar. The instructors even commented on it.

"You move like you've done this before," one said.

In a way, I had. For eight years, every time I'd taught a beginner how to roll properly, I'd been teaching survival skills disguised as martial arts fundamentals. Every time we'd practiced those "playful" exercises, we'd been developing exactly the physical vocabulary needed when everything falls apart.

But it went deeper than just the movements. In those tactical courses, I watched people give up when the exercises became challenging. They'd drop their weapons during stress drills, freeze when asked to make quick decisions under pressure, surrender when fatigue set in.

I recognized the pattern from aikido training. "Very often, losing is when a person simply gives up," I realized. In our dojo games—the ones where students had to last as long as possible rather than defeat an opponent—we'd been building something more valuable than technique. We'd been developing the mental conditioning that keeps you moving when everything goes wrong.

The revelation was stunning: while martial arts communities debated the effectiveness of various techniques, we'd been quietly training exactly what people need most in real crisis—the ability to move safely when the world becomes dangerous, and the mental strength to keep going when giving up feels easier.

Coming back transformed

When I returned to teaching, everything had changed—not the techniques, but my understanding of what we were actually doing.

Those "basic" exercises I'd taught for years weren't preparation for advanced aikido. They were advanced life skills, disguised as children's games. The crawling, rolling, falling, and spatial awareness we practiced weren't building toward something else—they were the destination.

I stopped talking about these movements as foundations for "real" aikido techniques. Instead, I began explaining what they actually develop: the ability to move safely through dangerous spaces, to recover quickly from unexpected falls, to stay mentally composed when physical challenges become overwhelming.

The students felt the shift. Parents noticed their children were more physically confident, better at recovering from stumbles, less anxious about rough play. Adult students mentioned improved balance and body awareness that carried into their daily lives in ways they hadn't expected.

But the deepest change was in my understanding of what aikido teaches about pressure and persistence. In our training games, the goal was never to defeat an opponent—it was to last as long as you could. "You win not when you can't last the longest, but when you lasted as long as you were able."

This philosophy, which had seemed almost quaint in peacetime training, revealed itself as profoundly practical wisdom. In real crisis, victory often means endurance. Survival comes from not giving up when circumstances become overwhelming. The mental conditioning we'd been developing through playful exercises proved more valuable than any specific combat technique.

Our instructor chat had transformed too. What began as coordination for seminars and rank promotions became a safety network where we checked on each other's wellbeing. The relationships built through years of shared practice—helping each other learn to fall, encouraging persistence through difficult techniques, celebrating small improvements—these bonds became lifelines when everything else felt uncertain.

What the games were really teaching

Now when I watch students practice those same exercises—crawling under bridges, rolling across mats, jumping over partners—I see something completely different than I did before.

They only seem like children's games because most aikido beginners are children. But these exercises develop physical preparation and endurance that extends far beyond martial arts. They're teaching fundamental survival skills: how to move your body safely through unpredictable environments, how to fall without injury, how to recover quickly when knocked down.

The movements trace back to the origins of aikido in traditional jujutsu, developed when warriors needed to fight effectively even when armored opponents made striking ineffective. Joint manipulation, balance disruption, and groundwork—the core elements disguised in our "basic" exercises—were practical responses to real combat situations where mere strength wasn't enough.

But perhaps more importantly, these exercises teach mental qualities that no amount of theoretical instruction can develop. Every time students struggle through a challenging drill and choose to continue rather than quit, they're building psychological resilience. Every time they help a partner learn a difficult movement, they're strengthening the community bonds that become crucial when individual strength isn't sufficient.

In Ukraine today, many civilians are learning basic tactical skills—not because they plan to become soldiers, but because these abilities might save their life or someone else's in an emergency. They're discovering what we'd been teaching all along: the most valuable skills are often the ones that seem most basic.

As there's a saying in Japan: the sword that might save your life once is worth carrying every day. Aikido's foundational movements—the ones that look like play—are skills worth practicing precisely because you hope you'll never need them for their original purpose.

But when you do need them, you'll be grateful they're already part of you.

The wisdom that was always there

Looking back, I realize the wisdom was never hidden. It was embedded in every exercise, present in every class, visible to anyone willing to see past the surface. We were always training for real life—we just didn't know it.

The children who giggled while crawling under their partners were learning to move through spaces too low for normal walking. The teenagers who competed to see who could roll the farthest were developing exactly the skills needed to minimize injury during unexpected falls. The adults who practiced jumping over obstacles were building the spatial awareness and physical confidence that translates directly to navigating dangerous terrain.

Even the philosophical elements—the emphasis on persistence over victory, the focus on mutual benefit rather than domination, the cultivation of calm presence under pressure—these weren't abstract ideals. They were practical preparations for handling real challenges with wisdom rather than just force.

What war taught me about aikido wasn't that our training was inadequate. It revealed that our training was more complete than we understood. The art had been preparing us all along, not just for physical confrontations, but for the broader challenges of staying human when circumstances become inhuman.

To instructors in peaceful countries, I offer this: continue practicing aikido at any age. What seems like play today might prove to be preparation tomorrow. The movements that appear most basic often carry the deepest wisdom. And the community you build through shared practice—the bonds formed by helping each other learn to fall and get back up—these connections matter more than any individual technique.

In the end, aikido taught me that the most profound skills are often the ones hiding in plain sight, disguised as something simpler than they really are. Sometimes it takes a crisis to reveal what was always true: we were never just practicing martial arts. We were learning how to live.

Editor's note: Oksana Kozakevych received her 3rd dan in April 2025 at an instructor seminar of the Ukrainian Aikikai Aikido Federation, continuing her development as both practitioner and teacher.

Know someone whose voice should be heard?

Share their story with us: 👉 https://aikicraft.substack.com/p/european-aikido-voices