When uke starts talking back

One instructor's experiment with breaking the silence tradition

"How did that feel?" I asked after a shomenuchi irimi nage. "Good," came the simple reply. "And that one?" After the next repetition: "Not so good."

That brief exchange during a class I was teaching challenged something I'd accepted without question for many years: that aikido training happens in silence, with learning flowing through the body alone.

TL;DR: Adding simple verbal feedback where uke evaluates their own experience can deepen awareness and improve ukemi quality without disrupting training flow.

I don't often have the opportunity to teach aikido classes. After 17 years of training, I've never had the desire to run a dojo. Aikido has become very important in my life, but it remains just one piece of my story.

On rare occasions, I get the chance to lead a class for my fellow aikidoka. Without regular teaching practice, my sessions are sometimes less structured than they could be. Less experienced teachers like myself tend to spend too much time explaining, often from the urge to share everything we know during those rare teaching moments.

One thing I try not to do is copy our sensei. Delivering the same lecture but worse seems pointless. Instead, I try different approaches, different themes, especially those not deeply covered in regular sessions. One of my favorites is working on being a great uke.

The problem I noticed

People today are increasingly disconnected from their own bodies, living more in our heads through constant digital communication. Aikido students are no exception.

Aikido offers excellent training to reconnect with physical awareness, but beginners (and honestly, we're all beginners until we reach some mythical mastery) often aren't sure what they're feeling. They go through the motions without fully engaging with the sensations their body provides.

I believe you cannot truly learn a technique as tori until you can perform the ukemi for it. The mistakes you make as tori are often the same ones you make as uke. Yet we rarely focus on developing uke awareness beyond basic safety.

The verbal feedback experiment came from a simple observation: if uke can't articulate what good technique feels like, how can they develop good ukemi? And without good ukemi, how can tori learn properly?

What I tried

I didn't arrive with an elaborate plan. The idea emerged from previous classes where we'd used thumbs up or thumbs down signals about whether a technique felt right. But this time, I wanted words.

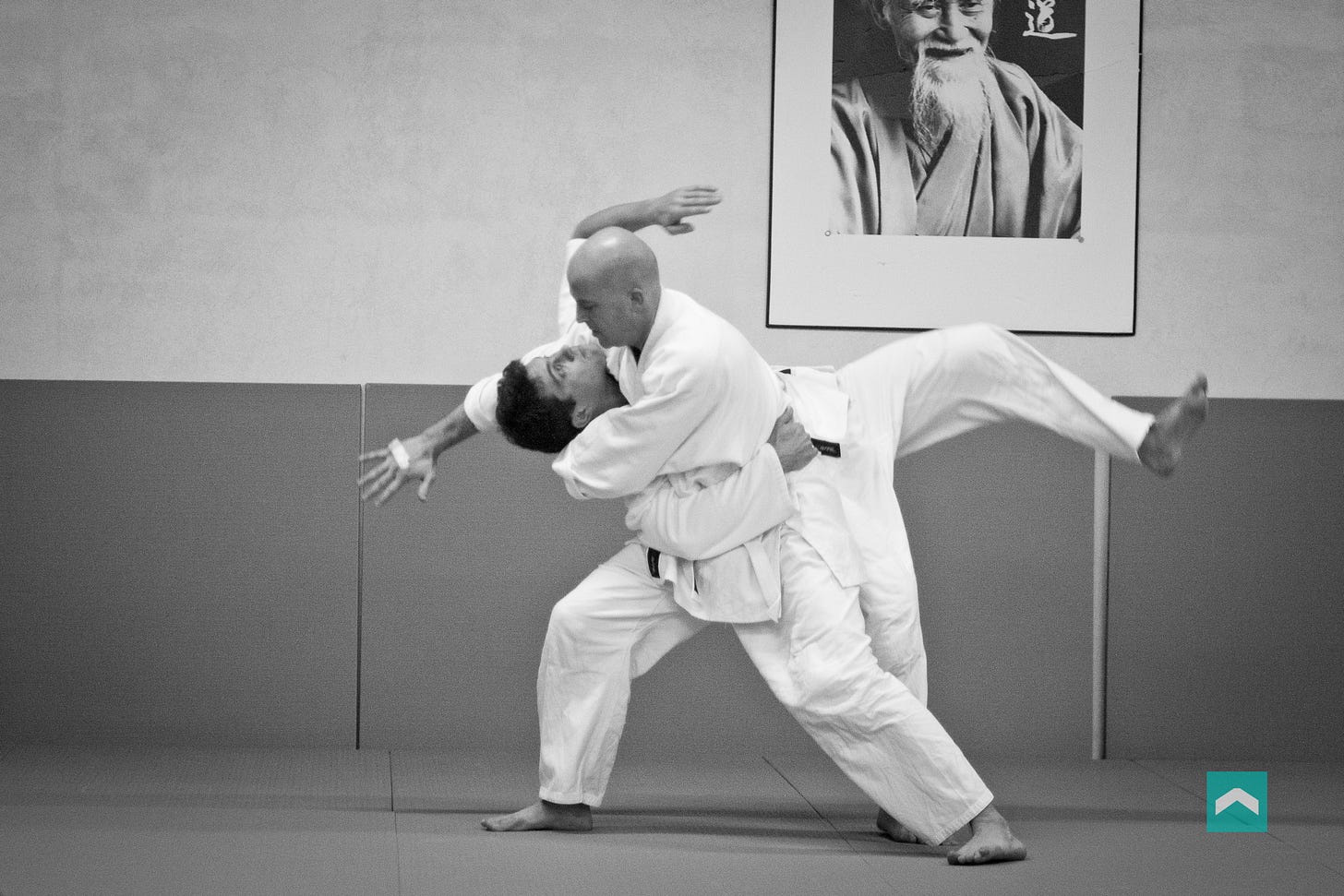

I chose simple techniques that students knew well: shomenuchi ikkyo, basic iriminage. I focused the instructions on uke quality rather than tori technique. "Give a committed, consistent attack. Stay connected throughout the technique."

After several repetitions, I asked uke to share briefly how they felt. Not technical analysis, not coaching for tori, just their personal experience: "Did that feel good or not good?"

The boundary was crucial: students could only evaluate their own experience, never their partner's technique. Teachers can evaluate others; students can only assess themselves. The goal was uke developing awareness of what quality technique feels like from the receiving end.

What actually happened

The students were receptive. Nobody resisted the idea, though I sensed some initial uncertainty about speaking during practice. The feedback was simple: "That felt good," "That side felt stronger," "That one was better."

I'll be honest: I didn't observe dramatic transformations in that single session. We only used this approach for about 30% of the class. But something shifted in the quality of attention. When students knew they'd need to articulate their experience, they seemed more present during the technique itself.

One pattern emerged: when students said "that felt good," both partners had visibly better posture and connection. When technique felt awkward or forced to uke, usually both partners were struggling.

Why silence exists and where it falls short

Aikido's traditional silence serves important functions. Unlike competitive sports, aikido has no clear winner or loser, no objective measure of "better" technique. Without boundaries, training can devolve into endless technical discussions where everyone becomes a teacher. The silence prevents that chaos.

But silence also creates frustration. People want to know if they're improving but lack clear feedback. In competitive sports, athletes receive constant feedback through scores and measurable results. In aikido, students often train for months wondering if they're developing any real skill.

A simple framework others might try

Based on this experiment, here's what worked:

Start with familiar techniques

Choose basic movements students know well. Complex techniques require too much cognitive load for effective feedback.

Focus on uke quality

Give clear instructions for committed attacks: "Make your attack smooth and constant, no gaps or hesitation."

Brief feedback moments

After 4-5 repetitions, ask: "How did you feel during that technique? Good, not good, or somewhere in between?" Keep responses short.

Clear boundaries

Students evaluate only their own experience, never their partner's technique. This prevents the session from becoming a critique of others.

Advanced addition

Try having students count steps aloud during technique execution. You'll be amazed how resistant people are to making any sound during training, even simple counting.

What this revealed

The experiment showed me that conscious collaboration between training partners accelerates learning. When uke takes responsibility for monitoring their experience and sharing it appropriately, both partners benefit. Tori receives immediate feedback about whether their technique creates the intended effect. Uke develops sensitivity to what quality technique actually feels like.

You cannot give good ukemi without knowing what good technique feels like. And you cannot develop that sensitivity without paying attention to your own experience as uke, not just tori's actions, but your own responses, sensations, and quality of engagement.

Both partners begin to understand that ukemi and technique are not separate skills. They are two aspects of the same collaborative exploration.

The goal isn't replacing traditional training methods but adding another tool for developing awareness. Some students learn best through pure physical repetition. Others benefit from occasional verbal reflection on their experience.

What's your experience with giving or receiving feedback during training? Have you found other ways to bridge physical practice with conscious awareness?

I really like this. I have been banging on about the position of Uke for a long time now. Here's my Substack piece from 2023 that gives my perspective. Some of your readers might find it useful. https://budojourneyman.substack.com/p/paired-kata-in-japanese-martial-arts